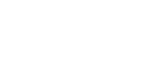

Title: “Unpublished Lishhaiahit – Kittitas (Leschi)”

Medium: Gold-toned Printing-out Print

Size: 14 1/4 x 11 1/4 inches | Framed: 29 x 25 inches

Original Curtis frame.

Negative #12

Signed: L.L.

Gold-toned Printing-out prints (more commonly known as albumen prints) are Curtis’ earliest and scarcest master exhibition prints. This handful of exquisite prints was printed in or proximal to 1900, when Curtis made his watershed journey to the Montana Plains to witness one of the final Piegan Sundances.

It is likely Curtis printed these images himself, in sunlight, while on that expedition. No other photographs are as close to Curtis’ own hands. It is believed there are less than 70 surviving examples of this process. Printing-out prints are the most coveted and important photographs Curtis produced. Artist: Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952)

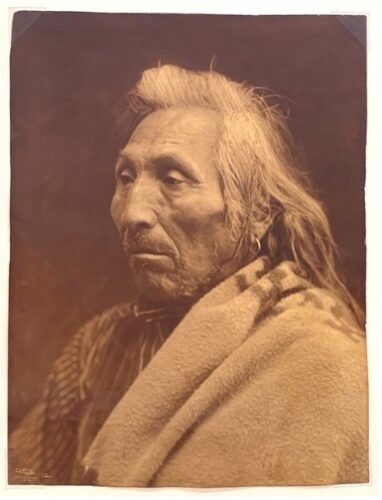

Title: “Homeward” (Puget Sound)

Medium: Gold-Toned Printing-out Print

Size: 5 5/8 x 7.81 inches | Framed: 16 x 20 inches

Signed L.L

Curtis never printed on an albumen paper. We have termed them albumen because the medium has technically been mislabeled. We simply use “albumen” for simplicity and consistency.

The early Curtis prints we call “albumen” are actually gelatin printing out prints. The process is the same for both albumen and gelatin printing out prints. The sensitized paper was placed in direct contact with a glass negative and exposed in strong light-usually sunlight. Then, the image formed on the paper while in contact with the negative and during its exposure to light. The final image was then toned with gold for color and permanence.

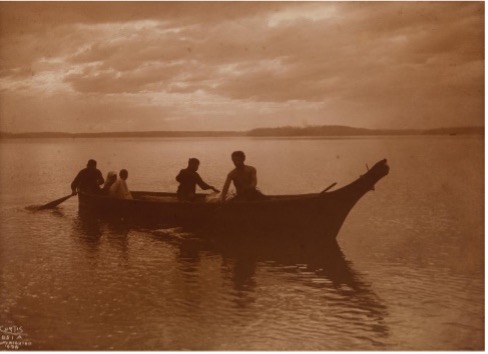

Title: “Unpublished Lishhaiahit – Kittitas (Leschi)”

Medium: Gold-toned Printing-out Print

Size: 7 x 5 1/4 inches | Framed: 16 x 13 1/4 inches

Frame is a vintage period frame.

Signed: L.L.

The difference between albumen and gelatin printing-out prints is in the papers. In both cases, a thin layer of emulsion sits above the paper and contains the light-sensitive silver salts which react with light to form the image. In albumen prints, that emulsion is made from whisked egg whites, and therefore called albumen. In gelatin printing out prints, the emulsion is made from gelatin, which is a starch. Gelatin prints are more stable than albumen prints because albumen decays very easily in the presence of moisture and light.