With a legacy half rooted in myth, it is of no surprise that the Chiricahua Apache leader Geronimo caught the eyes of both Edward Curtis and Andy Warhol, two esteemed artists in their own right. Geronimo was born near the Gila River headwaters in New Mexico and became a warrior after his mother, wife, and three children were killed in a raid by Mexican soldiers in 1858. The legend goes that the vengeful Geronimo could make himself invisible in battle and defy bullets, injury, and capture. However, the Apache warrior surrendered in 1886, marking the formal end of organized military resistance by Native Americans to their conquerors.

With a legacy half rooted in myth, it is of no surprise that the Chiricahua Apache leader Geronimo caught the eyes of both Edward Curtis and Andy Warhol, two esteemed artists in their own right. Geronimo was born near the Gila River headwaters in New Mexico and became a warrior after his mother, wife, and three children were killed in a raid by Mexican soldiers in 1858. The legend goes that the vengeful Geronimo could make himself invisible in battle and defy bullets, injury, and capture. However, the Apache warrior surrendered in 1886, marking the formal end of organized military resistance by Native Americans to their conquerors.

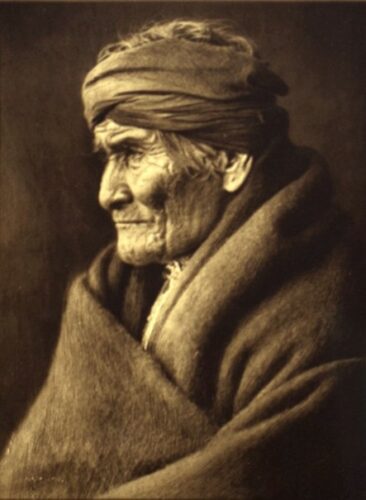

Edward Curtis had the privilege of meeting Geronimo in 1905 when they were both invited to attend President Theodore Roosevelt’s inauguration. Despite Geronimo’s status as a prisoner of war and only being able to leave Fort Still with government permission, the fire had not left the 76-year-old Apache warrior’s eyes. Infatuated with Geronimo’s resilience while simultaneously outraged by his forced assimilation, Curtis resolved to transmit the truth of this hardened man through his camera. After persuading Geronimo to pose for a separate sitting Curtis wrote, “the spirit of the Apache is not broken.”

In Curtis’ 1905 photograph, Geronimo is captured in profile and caught in a moment of retrospection. He is wearing only a cloth headband (as he wore in his youth) and a rough woolen blanket that envelops his entire upper body. The lack of ornamentation and formal regalia paints the famous icon in a rather modest light and creates a solemn mood as the viewer reflects alongside Geronimo. The plain background and simple garb also serve to draw attention to Geronimo’s own character. Even with only half his face visible, the viewer can easily identify Geronimo’s defiant and prideful attitude in subtleties such as his pressed lips, clenched jaw, and furrowed brow. The deep lines of his face tell the story of his life and his refusal to give up nothing for sympathy.

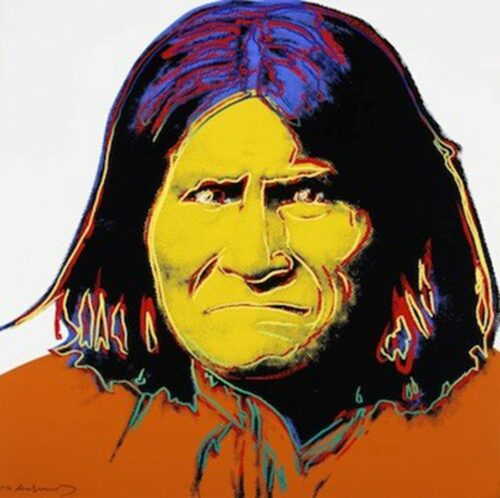

Alternatively, Andy Warhol’s 1986 “Geronimo” from his Cowboys and Indians series is a screen print based on an 1887 photograph by A. Frank Randall. In the original photo, Geronimo is kneeling holding a rifle surrounded by southwestern shrubbery; yet, in truth, Geronimo had already surrendered and been captured as a prisoner of war at the time this photo was taken. Warhol uses this image but crops it to reveal only Geronimo’s face. Similar to Curtis’ rendition, this close-up emphasizes Geronimo’s own identity. In this portrayal, the viewer faces the full force of Geronimo’s direct glare. Gestural lines only accentuate his strong facial features and angered expression. Warhol’s print is also rendered in bold and vibrant colors, a fiery red, yellow, and deep purple made imposing by the little negative space. The use of bright hues is emblematic of Warhol’s Pop Art style and transforms the historical figure into a celebrity icon. This romanticized view of the American West mirrors that of the public and evokes issues of exploitation, conflict, and historical representation.

While both artists successfully capture Geronimo’s spirit in their artwork, they employ entirely different means. Edward Curtis’ “Geronimo” yields a more introspective effect, whereas Warhol intentionally commodifies Geronimo. However, it is evident in viewing these pieces that both Curtis and Warhol shared a fascination and deep appreciation for this tough and proud Apache Leader.

Both “Geronimo” pieces are available now at Valley Fine Art. Please contact info@valleyfineart.com for further information.